Causal Emergence in Biological Networks

Table of Contents

Overview #

To understand that the field determines the behaviour of any local process or constituent, it is necessary fundamentally to modify modern science by revising our theory of first principles in order to justify the unity of Nature as a causal factor. Without this revision of our most elemental concept of Nature, as conceived by science, all field theories, whether in physiology or physics, are mere verbiage.

— Harold Saxton Burr1

Causal emergence refers to the process by which higher-level collective behaviors or properties emerge as a result of the interactions between lower-level components.2 It is a model for representing the information transfer between scales, where information flows from the microscale to the macroscale, producing emergent patterns or behaviors that cannot be fully explained by the behavior of individual components at the microscale. The macroscale representation of the interactions between components at the microscale provides new insights into how the system operates as a whole, beyond what can be understood from examining the behavior of individual components.

In this framework, information conversion is the transformation of one type of information into another type of information as a result of changes in scale of spatial organization or modelling. Changes in scale, such as the transition from a microscale to a macroscale, can result in the conversion of causally irrelevant information (such as the uncertainty of state transitions) into causally relevant information (such as effective information). Information conversion takes place between types of information, the conversion of redundant information into synergistic information, through changes in modelling. The process of information conversion is a key aspect of emergence and it is possible to quantify this conversion through various information-theoretic measures.

Below, I’ve chosen to analyze gene regulatory networks as a microscale using this framework. The data presented here shows decreases in the uncertainty of state transitions across these networks as their macroscale representations are created.

The macroscale representations created here can provide insights into the relationships between gene-protein interactions and higher scales of biological organization such as tissues, organs, etc by showing how the original scale is being influenced by causally relevant information organized at the higher scale.

By analyzing the macroscale of a gene reguatory network, we can see hints to the information flow that anchors the next highest scale of spatial organization to this original scale, and determine how the higher scale is affecting the behavior of the system at the original scale.3 This information can be used to better understand how the two scales are linked and how changes in the higher scale can impact the interactions at the original scale. Additionally, the macroscale representation can highlight areas of the network that may be particularly sensitive to changes in the higher scale, providing insight into where interventions at the higher scale could have the greatest impact on the system at the original scale.

Not only am I interested in how redundant information is transformed into synergistic information at higher scales of spatial organization, but I am also exploring how redundant information is converted to synergistic information at its original scale as a product of time, especially in these gene regulatory networks. My hypothesis is that through aging, redundant pathways in the GRNs of our cells are slowly erased through the changes in epigenetic modificaitons, serving to block certain pathways as a means of adhering to the free energy principal.4

Going back to the idea of causal emergence, the unaswered question I have in this regard is the direction of causality for promoting these epigenetic modifications. This is why in addition to GRNs, I choose to run the same network analysis on bioelectricity-integrated gene and reaction(BIGR) networks.5 It has been shown that there is a direct correlation between epigenetic modifications and the regulation of intercellular communication through ion channels and gap junctions6,7,8, however it is unknown whether the buildup of these markers are themselves a downstream process effected by intercellular communication through these channels. This would imply that they serve as a feedback loop to eachother, wheras if the promotion of modifications was being instigated at the GRN/DNA level exclusively, then the changes in intercellular communication over time related to epigenetic modifications would be causally downstream of GRN interactions, and not causal to them.

For the sake of thinking about where to intervene and alter these modifications, I seek to answer the question of which is more causal to the other.

Gene Networks #

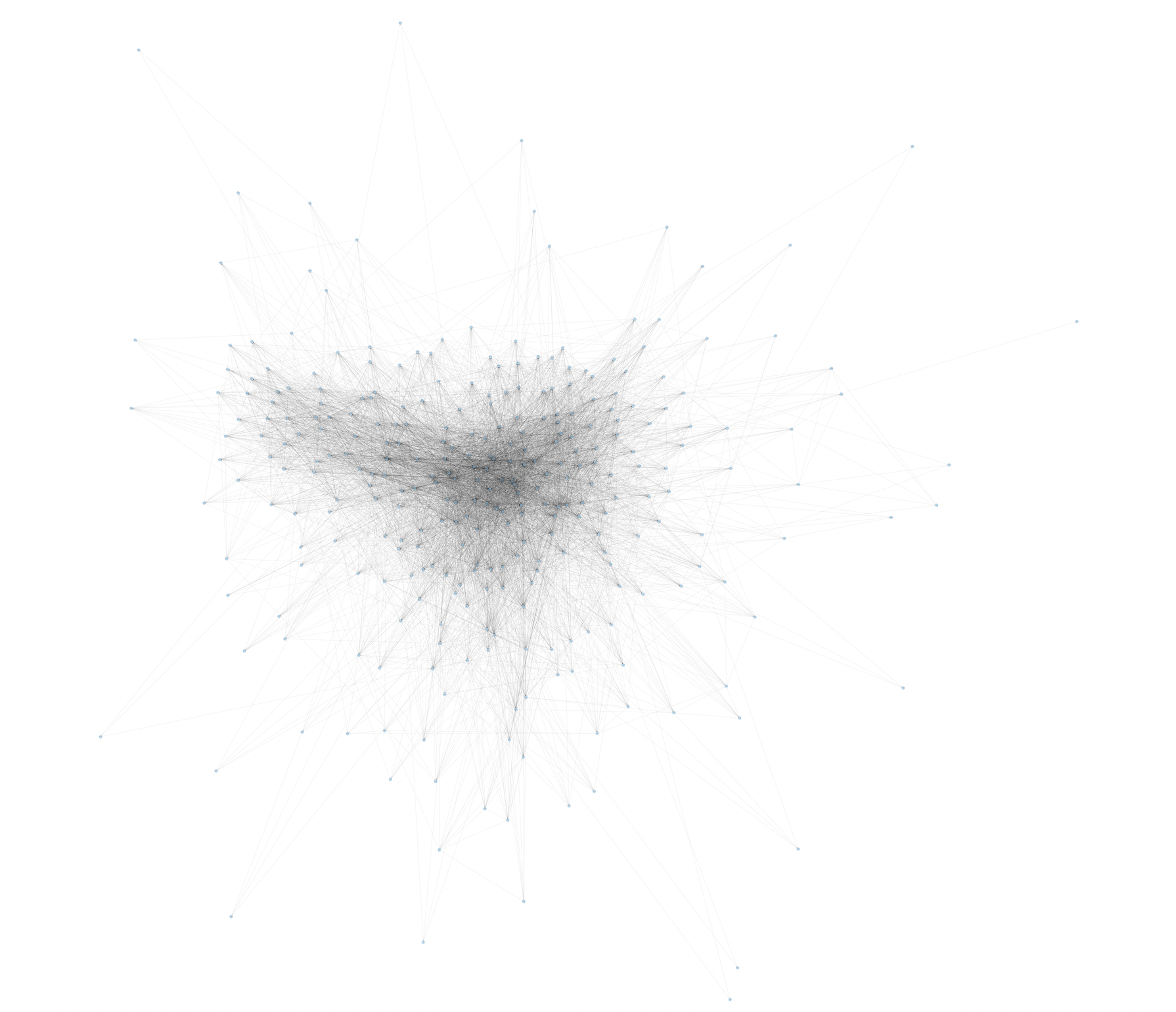

Before: #

After: #

What I’m doing #

- Take a base gene dataset.

- Use STRING to create a graph of these genes and their pathways with wieghted edges.

- Use this package to determine effective information for this graph9:

1 2 3 4 5 6from ei_net import effective_information import networkx as nx import numpy as np G = nx.GRAPH() EI_micro = effective_information(G) print("EI micro: %.6f"%EI_micro) - Create a macro graph using the same package. More details on how to do this here.

- Return difference between effective information across 2 graphs as well as e:

1 2 3eff_gain = (EI_macro-EI_micro)/np.log2(N) print("Effectiveness gain: %.6f"%eff_gain) Effectiveness gain: {VALUE} - Repeat until no more macro nodes are found.

Humans — #

Aging #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.335729

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 306 | 7862 | 2.7722478691230394 | N/A |

| 1 | 215 | 6730 | 2.8410909848914425 | 0.008337 |

| 2 | 188 | 5574 | 2.850469 | 0.009473 |

| 3 | 188 | 5148 | 2.852802 | 0.009755 |

| 4 | 177 | 4645 | 2.855296 | 0.010057 |

| 5 | 163 | 3913 | 2.860143 | 0.010644 |

| 6 | 144 | 2960 | 2.860143 | 0.010644 |

| 7 | 136 | 2620 | 2.874134 | 0.012339 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.405523737036814

Senescence #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.486386

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 259 | 2585 | 3.899266239854304 | N/A |

| 1 | 184 | 2355 | 3.99960383896453 | 0.012516 |

| 2 | 180 | 2262 | 4.002437 | 0.012869 |

| 3 | 176 | 2155 | 4.003378 | 0.012987 |

| 3 | 174 | 2066 | 4.004505 | 0.013127 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.53802705908

If an intervention works for a macronode, with 2 different internal causal pathways, then we may be able to identify more fine grained interventions:

Additionally, what nodes get grouped into a macro-nodes tells us what interventional targets are meaningful within the system. Consider that of the two macro-nodes in the system {μ1, μ2}, each requires the activation of exogenous canWnt II. However, their set of underlying nodes are differentiated solely by the concurrent activation of Foxc1_2, which is not upregulated in μ1 and is upregulated in μ2. This tells us that it is solely Foxc1_2, rather than any other element in the network, that determines which causal path the network takes as long as exogenous canWnt II is activated. The macro-nodes capture which differences are actually relevant to the intrinsic workings of the system itself. cc: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19420889.2020.1802914

Mus Musculus (Mouse) — #

Aging #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.434615

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 130 | 1056 | 3.0520255784285086 | N/A |

| 1 | 92 | 928 | 3.133283 | 0.011571 |

| 2 | 86 | 803 | 3.138779 | 0.009473 |

| 3 | 83 | 767 | 3.139050 | 0.012392 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.48975792415

Physiology #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.458635

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 494 | 9025 | 4.104038136973786 | N/A |

| 1 | 322 | 6508 | 4.240497089574829 | 0.015250 |

| 2 | 313 | 6161 | 4.243813 | 0.015620 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.511918

Drosophila (Fruit Fly) — #

Aging #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.546897

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 187 | 1303 | 4.127372843455749 | N/A |

| 1 | 128 | 930 | 4.294786 | 0.022183 |

| 2 | 122 | 853 | 4.29722214296244 | 0.022506 |

| 3 | 83 | 767 | 3.139050 | 0.012392 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.62002380607

Stem Cell Genes #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.511734

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 285 | 2533 | 4.173097660494712 | N/A |

| 1 | 259 | 4021 | 4.202267897429325 | 0.003577 |

| 2 | 258 | 3989 | 4.202562037958708 | 0.003613 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.524584

Caenorhabditis elegans #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.559496

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 825 | 10655 | 5.420533831393049 | N/A |

| 1 | 620 | 9491 | 5.567058824717181 | 0.015124 |

| 2 | 611 | 853 | 5.568796385519166 | 0.015303 |

| 3 | 609 | 9450 | 5.569021173547727 | 0.015327 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.602037

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Incomplete) #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.535618

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 931 | 14689 | 5.282608841216231 | N/A |

| 1 | 761 | 15840 | 5.408062463177776 | 0.012720 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.565002

BIGR Networks #

BIGR Networks = bioelectricity-integrated gene and reaction networks.

The functional properties of BIGR networks generate the first testable, quantitative hypotheses for biophysical mechanisms underlying the stability and adaptive regulation of anatomical bioelectric pattern.9

What I’m doing #

- Take a base BETSE config file with a GRN specified.

- Run the simulation and output a network of the resulting bioelectric circuit.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8model.run_pipeline() ...(wait for simulation) grn = model.phase.sim.grn.core grn.init_saving(model.phase.cells, model.p, nested_folder_name='GRN') savename = grn.imagePath + 'OptimizedNetworkGraph' + '.svg' graph_pydot.write_svg(savename, prog='dot') graph_network = networkx.nx_pydot.from_pydot(graph_pydot) networkx.write_gml(graph_network, "graphname.gml") - Use this package to determine effective information for this graph8:

1 2 3 4 5 6from ei_net import effective_information import networkx as nx import numpy as np G=nx.read_gml("graphname.gml") EI_micro = effective_information(G) print("EI micro: %.6f"%EI_micro) - Create a macro graph using the same package. More details on how to do this here.

- Return difference between effective information across 2 graphs as well as e:

1 2 3eff_gain = (EI_macro-EI_micro)/np.log2(N) print("Effectiveness gain: %.6f"%eff_gain) Effectiveness gain: {VALUE} - Repeat until no more macro nodes are found.

Tissues that have as little change as possible through time, but with high variance between cells10 #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.664508

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 26 | 24 | 3.1234786725698864 | N/A |

| 1 | 20 | 18 | 3.382072 | 0.055015 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.782538

Tissue that is stable on a specific pattern10 #

“Smiley” Pattern: #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.749480

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 23 | 19 | 3.3903195311147827 | N/A |

| 1 | 20 | 17 | 3.417340 | 0.005973 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.790698

“Bullseye” Pattern: #

Initial Effectiveness: 0.678185

| Run | Nodes | Edges | Effective Information | Effectiveness Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 17 | 15 | 2.7720552088742005 | N/A |

| 1 | 16 | 14 | 2.823068 | 0.012480 |

Final Effectiveness: 0.705767

To Do #

- Run against more complex GRN simulations in BIGR networks.

- Test Resilience and Prospective Resilience of all generated networks: https://github.com/jkbren/presilience

Tools #

Greedy Algorithm for identifying subgraphs: https://github.com/jkbren/einet

The greedy algorithm used for finding causal emergence in networks is structured as follows: for each node, vi, in the shuffled node list of the original network, collect a list of neighboring nodes, {vj} ∈ Bi, where Bi is the Markov blanket of vi (in graphical models, the Markov blanket, Bi, of a node, vi , corresponds to the “parents,” the “children,” and the “parents of the children” of vi). *This means that {vj} ∈ Bi consists of nodes with outgoing edges leading into 10 Complexity vi, nodes that the outgoing edges from vi lead into, and nodes that have outgoing edges leading into the out-neighbors of vi. For each node in {vj} , the algorithm calculates the EI of a macroscale network after vi and vj are combined into a macronode, vM. If the resulting network has a higher EI value, the algorithm stores this structural change and, if necessary, supplements the queue of nodes, {vj}, with any new neighboring nodes from vj’s Markov blanket that were not already in {vj}. If a node, vj, has already been combined into a macronode via a grouping with a previous node, vi , then it will not be included in new queues, {vj }′ , of later nodes to check. *The algorithm iteratively combines such pairs of nodes until every node, vj, in every node, vi’s Markov blanket, is tested.

Protien and gene regulatory interaction db: https://string-db.org/

Data Availability #

Aging Genes for Multiple Species: https://genomics.senescence.info/genes/index.html

Senescence Genes for Humans: https://genomics.senescence.info/cells/

Supplementary files for BIGR network simulations: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.10.23.513361v1.supplementary-material

Citation #

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Anderson, Benjamin, “Causal Emergence in Biological Networks”, TheBenjam.in (2022-07-23), available at https://www.thebenjam.in/research/.

Changelog #

August 22, 2022 — Added physiology data for mice and stem cell genes data for drosophilia.

September 14, 2022 — Added quote at the beginning and citation to Free Energy Theory of Aging write-up.

October 25, 2022 — Removed ‘Open questions / Areas to Explore’ section. Added ‘BIGR networks’ section. Edited ‘Overview’ section.

February 4, 2023 — Rewrote ‘Overview’ section to add additional context regarding why this research is relevant to seeking more effective intervention strategies in biological systems. Updated lead text.

Burr, Harold Saxton. Blueprint for Immortality: The Electric Patterns of Life. ↩︎

Varley Thomas F. and Hoel Erik 2022 Emergence as the conversion of information: a unifying theory Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 380: 20210150.20210150 ↩︎

Brennan Klein, Erik Hoel, Anshuman Swain, Ross Griebenow, Michael Levin, Evolution and emergence: higher order information structure in protein interactomes across the tree of life, Integrative Biology, Volume 13, Issue 12, December 2021, Pages 283–294, https://doi.org/10.1093/intbio/zyab020 http://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2021.0150 ↩︎

Anderson, Benjamin, “The Free Energy Theory of Aging”, TheBenjam.in (2022-09-05), available at https://www.thebenjam.in/research/. ↩︎

Pietak A, Levin M. Bioelectric gene and reaction networks: computational modelling of genetic, biochemical and bioelectrical dynamics in pattern regulation. J R Soc Interface. 2017 Sep;14(134):20170425. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2017.0425. PMID: 28954851; PMCID: PMC5636277. ↩︎

Masahito Oyamada, Kumiko Takebe, Yumiko Oyamada, Regulation of connexin expression by transcription factors and epigenetic mechanisms, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, Volume 1828, Issue 1, 2013, Pages 118-133, ISSN 0005-2736, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.12.031. ↩︎

Tseng, A.-S. and Levin, M. (2012), Transducing Bioelectric Signals into Epigenetic Pathways During Tadpole Tail Regeneration. Anat Rec, 295: 1541-1551. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.22495 ↩︎

Pai, V. P., Martyniuk, C. J., Echeverri, K., Sundelacruz, S., Kaplan, D. L., & Levin, M. (2015). Genome-wide analysis reveals conserved transcriptional responses downstream of resting potential change in Xenopus embryos, axolotl regeneration, and human mesenchymal cell differentiation. Regeneration (Oxford, England), 3(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/reg2.48 ↩︎ ↩︎

Klein, B., Swain, A., Byrum, T., Scarpino, S. V. & Fagan, W. F. (2022). Exploring noise, degeneracy and determinism in biological networks with the einet package. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 799– 804. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13805 ↩︎ ↩︎

Exploring The Behavior of Bioelectric Circuits using Evolution Heuristic Search. Hananel Hazan, Michael Levin. bioRxiv 2022.10.23.513361; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.23.513361 ↩︎ ↩︎